Pupils with SLCN in primary schools

Most adults working in primary schools will come into daily contact with pupils who have communication difficulties and, in your role as a specialist teacher, there is much you can do to support colleagues working with children with SLCN.

This unit covers the following:

- Those areas of communication which may be particularly problematic for primary-aged children with SLCN

- Effective strategies for developing pupils’ speech, language and communication skills in primary school

- The wider implications of SLCN for pupils’ outcomes

- Transition from primary to secondary school

Prevalence of SLCN in primary schools

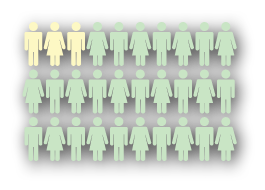

SLCN accounts for almost 23% of pupils with statements in primary schools, making it the most prevalent form of SEN in that age group. This means that most primary school staff will come into daily contact with pupils who have some form of SLCN.

On average, every primary school class will have 2 or 3 pupils with SLCN.

In some areas of the country, as many as 1 in 3 primary-aged children have a language delay.

The impact of SLCN on primary school pupils

Understanding and formulating spoken language

The impact of difficulties in understanding spoken language can be wide-ranging. Pupils’ experiences in school can include:

- Struggling to understand when a teacher gives them instructions or explains new concepts.

- Being unable to process the various phrases that are new to all children when they start primary school, many of which are open to literal interpretation, for example 'fold your arms' or 'break time'.

- Difficulties in processing information that has been given verbally, which may mean that pupils struggle to follow more than one instruction at a time.

Additionally, some pupils may not be able to formulate spoken language. Communication in school requires the following skills and abilities:

- Understanding the grammatical rules of sentence construction.

- Using the right words in the right order.

- Having age-appropriate levels of vocabulary; learning vocabulary has been identified as one of the most significant difficulties for pupils with SLCN.

Government initiatives have recognised the importance of paired and classroom talk among pupils to enhance learning. An inability to communicate efficiently means that some children with SLCN are missing vital learning opportunities.

If their language skills are not proficient enough to be used as a learning tool, children are in a position where they will fail some tasks before they've even begun. This is frustrating for the child and may have longer-term implications for their self-esteem and engagement with learning; it may also influence the way that they are perceived by their peers.

Language and literacy skills

- Access to the curriculum

- Later academic success

- Positive self-esteem

- Improved life chances

Language for social development

- Clarify thoughts to others

- Negotiate roles in play

- Organise activities

- Communicate feelings

- Make and maintain friendships

- Resolve disagreements

SLCN and behavioural, emotional and social difficulties

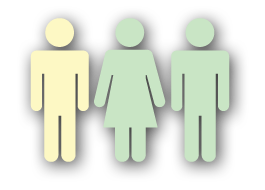

There is increasing evidence of a link between SLCN and BESD, with several studies showing that children with an early diagnosis of language and communication difficulties are more likely to have behavioural problems. Other studies of children with BESD found that 3 out of 4 had significant language deficits.

See the Talking Point website for further discussion on the links between communication and behaviour.

A structured approach to teaching language

This video features Rachel Drinkwater, lead language practitioner at Bankside Primary School in Leeds, teaching a group of pupils of mixed ability. A high proportion of Bankside’s 700 pupils have English as a foreign language and SEN, and Rachel explains how using ECAT strategies can encourage children to develop their use of language.

This clip relates to the video task in your PDF of unit 12.

Show transcriptNarrator

Bankside is a large inner city Primary School in Leeds of which a high proportion of its 700 pupils have English as a foreign language and Special Educational Needs.

Rachel

Are you ready Sahill?

Narrator

Rachel Drinkwater is a Reception Class Teacher.

Rachel

Within the cluster of schools in the Leeds area, we are developing the ECAT, Every Child a Talker, strategies. So within every setting, a lead language practitioner which here at Bankside is myself, has it put into place, and the lead language practitioner’s job, so my job role, is to feed through the ECAT strategies down to other teachers, and nursery nurses, and teaching assistants, within those settings to ensure that the ECAT strategies are being used, carried through and developed in order to ensure our children’s progress in talking.

So it’s the practitioner’s role to be engaged with the child, to be down at their level, to be commenting, asking open ended questions, to ensure that you’re getting full sentences back from the children, to make sure that they are using their voices more than anything, so that their language develops.

Classroom interaction

Rachel: Whisper into your hand what you’re going to do today.

Rachel

So this morning I’m with a group with a range of ability. I had 2 SEN children, I’ve got 3 higher ability children in that group, and the rest are middle ability children. And we use these sessions to get the children talking and to get them interested in different things.

Classroom interaction

Rachel: Can we all say ‘Shell’?

Pupils: Shell/Shelf

Rachel: It does sound a little bit like a shelf, but it’s not a shelf, it’s a shell.

Pupils: Shell!

Rachel: “sh” “eh” “ll”

Pupils: “sh” “eh” “ll”

Rachel: Get your chopping boards out.

All together: “sh” “eh” “ll”. Shell. Do it again.

Rachel:

We’ve actually got a brand new sandpit, that’s why I decided to choose shells. And then just to give each child a shell, it’s making sure that every child has the opportunity to be part of the lesson. And then we’re using describing words and vocabulary, and then they use their thinking fingers first, so that they’re thinking, and then they talk to their partners so they’re sharing ideas, which gives everybody a chance to be part of it. Then we share ideas back.

Rachel

Rachel: Rumana, what do you think might be in the chest?

Rumana: Treasure

Rachel: “I think…”

Rumana: I think it’s going to be a treasure.

Rachel

So it shows how involved and how interested, how sustained the learning was, is that a child said this morning, I’m going to go and bury my shell, and she went straight outside and buried her shell. So, it’s child initiated, they’re all involved, and it’s a great way of using language and talk.

Classroom interaction

Rachel: Owais, say it again.

Owais: Spin it

Rachel: You want to spin your shell. Show me.

Rachel

Owais has got cerebral palsy, and his speech and his language is very delayed as well within pronunciation and his vocabulary. Sahill is the same; his speech and language is very delayed.

Classroom interaction

Sahill: I can see

Rachel: You can see. What can you see?

Sahill: It’s walking

Rachel: Pardon

Sahill: It’s walking

Rachel: The shell is walking.

Rachel

He’s working at scale point 4 and 5 on the early years’ foundation stage. It’s important, I think, that they’re involved in the whole class. It’s nice to see because I taught Sahill last year, and Sahill wouldn’t have even sat down and joined in last year. He was involved for a good 15 minutes. I think they were really involved this morning which is brilliant. They were focussed, they were on task, they knew what the learning objective was and they were doing it. Then they shared their ideas. They were willing to share and use their loud and proud voice to share with the other children.

Quality first teaching is about thorough rigorous planning. You know where your children are and where they need to get to, you know your objectives, your success steps, vocabulary, that’s the main focus at our school. Differentiating, so making sure every child is being covered, from your low SEN children, your middle ability and your higher ability, making sure there’s a challenge in place for your higher ability, and they all achieved the learning objective.

I think my lesson this morning was a good example of quality first teaching.

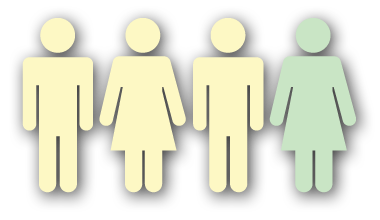

New

- Vocabulary

- Subjects

- Curriculum

- Teachers

- Teaching styles

- Organisation

- Routines

- Social groups

Meeting the needs of pupils with SLCN

A 2005 study of primary school teachers found that 60% lack confidence in their ability to meet the needs of pupils with SLCN.

View source

Source

Sadler, J (2005) Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs of the Mainstream Teachers of Children with a Pre-school Diagnosis of Speech/Language Impairment, Child Language Teaching and Therapy, Volume 21, 2

Good practice strategies

Audit

CloseAuditing the learning environment will alert you to any areas that could be improved to better support pupils with SLCN.

Creating opportunities

CloseSchool staff can give pupils the chance to become confident in using language in different situations and with different people.

Knowledge

CloseIt is important that school staff know about the language development of pupils with SLCN and are aware of the demands that the school environment places on these pupils.

Adapting language

CloseSchool staff who are aware of the specific difficulties experienced by pupils with SLCN are more able to adapt the language they use to ensure it is accessible to all pupils.

Teaching

CloseSteps should be taken to develop pupils' skills in:

- Monitoring their own understanding.

- How to interact productively.

Planning

CloseIt is important that school staff plan for a child with SLCN, particularly around times such as transition, when additional demands may be put on the pupil's language and communication skills. Throughout planning processes, it is crucial that staff take time to involve the pupil in any decisions that are taken. Teachers can raise a pupil's awareness of their strengths and needs, but the pupil can also offer key insights into the impact of their SLCN and measures that can be taken to support them in school.